I know two particular people who are Irish optimist, meaning they always recognize that things could be worse. One of them once told me, "Everyday you have your manhood is a good day," as well as, "Your dick could be like a hot dog in a microwave." It strikes me that this same principle is never used when thinking about the religious, right winged, conservatives. Mostly the big complaint is that they want to destroy scientific research, progress, and digress society back from our technological advancements. They want to stop teaching evolution, end genetic research, stem cell testing, et cetera. Thank goodness these people are the worst we have to deal with, because it could certainly be worse. Imagine if that religious fervor was directed toward the advancement of technology and scientific knowledge in all its potential and possibilities. It would be an understatement to say we would all be having a bad time.

Admittedly science has produces many wonders, and have found countless beautiful properties of the natural world. We can grow a human tracheae with stem cell injections. We are on the verge of curing HIV. We can harvest energy from the wind and the sun. We can travel faster than the speed of sound. We can make a dragonfly grow to be almost four times its normal size. We can predict solar storms and sun spot cycles. I recently found out today why I only breathe through one nostril at a time. It's called nasal cycles and they occur about every four hours. Awesome! (Literally awe-some).

But Oppenheimer knew how far science can go. He knew the horrors of splitting an atom. He knew the nightmares science can create. It is an ethical problem among scientists as to whether the potential of certain scientific research should be ever known. Oppenheimer had even considered deliberately rendering the data for the Manhattan Projected flawed, because he felt these were areas of science that no one should tamper with. He only changed his mind because he feared the Germans would have a bomb as well, and they would not hesitate to use it. The marketing side of technology tends to use this argument: any and all technology should be discovered and documents, but how that technology is used is not our concern. No, it is a concern, and it is a huge ethical problem. If we could created artificial black holes of a significant size, would it be wise to test that on earth? Is it even ethical to test biological toxins and poisons for weaponry on planet earth?

Imagine the religious zealousness mixed with the horrors science and technology can achieve. We can hate the religious right for hating science, but it must be admitted that it is a relief they don't direct that same fervor towards the advancement of science at any and all costs. We should fear more any cult that embraces science and technological advancement to whatever end than those who just want to do away with it. It is far better for the human race to be set back a hundred or two years than to wipe ourselves out with anything we cannot possibly imagine at this time.

I believe in scientific progress, but I also admit that science and technology have a dark side. Oppenheimer knew that all too well.

"Now I have become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

~Bhagavad Gita, 11: 32

Friday, June 29, 2012

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Prometheus: Asking Stupid Questions

I recently had the misfortune of watching Prometheus, a movie I had expected Ridley Scott would use to further push the potential science fiction. Needless to say he didn't. Scott has been known throughout his career of reinventing science fiction. Alien left us with questions on the preciousness of life, the consequences of death, and the expendability of human life. In fact, Alien can be viewed in two ways: as a story of evil corporations and their employees being expendable, or as one big metaphor for procreation, impregnation, gestation, painful childbirth, maturation, and death. Bladerunner also explores expendability of life, but more especially with slaves, and brings forth the question of are we allowed to kill what we create?

While some of these things were present in Prometheus, the overwhelming question of the movie was ultimately futile: where did we come from and why? Why is this a stupid question? To put it simply, it's a question that isn't exactly answerable. It has no end, and if it does have an end, then the end of the answer is a cop-out.

Prometheus posits that some other alien race created us. Then they wanted to kill us. Why? Who know. Scott never answers this question. Bladerunner and Alien ask if this is ethical, but never asks why were we created. Prometheus doesn't care if it's ethical to kill that which you created, but rather where did we come from and why. So Dr. Shaw, who is Christian, clearly has some faith issues. She believes aliens made us, but she still believes in Christ her savior. Exactly why Scott has thrown religion into this film is beyond me. He usually sticks to religious ambivalence or a near atheistic point of view in his films. But this one, Christianity wins (I guess Scott is getting old and is turning back to the Bible), or at least isn't rejected. We're off to meet our maker, who isn't God, but we still believe in God... right? Androids don't worship God, nor do they worship us (they serve us).

If we were created by aliens (because fuck Darwin), then the obvious question is: who created them? More aliens? Who created them? More aliens? It's a vicious cycle that usually terminates with God. God created everything. But when asked who created God, the trump card is pulled, because nothing created God. God always existed. I may believe in God, but the God-trump-all-card is not a worthy argument in scientific debate.

Why is this stupid to ask? Because it has no real answer, and any answer is a cop-out. I call it idle philosophy, a term I get from John Milton. Asking these sorts of questions get us nowhere, at least nowhere satisfying. We either end up with no answer ("I don't know where we came from"), an answer that is a paradox ("We created God who then created us"), or an illogical conclusion, a cop-out ("God did"). This is why Zen Buddhists usually give strange answers to certain questions. If you ask a Zen Master who created us, they would probably respond with "Mu." It's not an answer because there isn't one. If you ask a stupid question you get a stupid answer, so you shouldn't ask them.

Overall the movie was disappointing. It's okay for a movie to ask questions and not answer them, but it is supposed to make us think (something Borges does a lot in his short stories). But to barely give a premise of philosophy, throw around a bunch of vague questions, and NEVER EXPLAIN THE ALIEN! leaves me a bit disgruntled. Are we supposed to be looking at these questions on the origin of life from a religious point of view or a panspermic one? (Because, again, fuck Darwin). Are we supposed to think of ourselves as cattle or a wrongful experiment? Who exactly is the protagonist, so that we can understand which point of view to weigh more heavily? Is it Shaw or David or the Engineers?

Was there even a philosophy? Was there even a plot?

While some of these things were present in Prometheus, the overwhelming question of the movie was ultimately futile: where did we come from and why? Why is this a stupid question? To put it simply, it's a question that isn't exactly answerable. It has no end, and if it does have an end, then the end of the answer is a cop-out.

Prometheus posits that some other alien race created us. Then they wanted to kill us. Why? Who know. Scott never answers this question. Bladerunner and Alien ask if this is ethical, but never asks why were we created. Prometheus doesn't care if it's ethical to kill that which you created, but rather where did we come from and why. So Dr. Shaw, who is Christian, clearly has some faith issues. She believes aliens made us, but she still believes in Christ her savior. Exactly why Scott has thrown religion into this film is beyond me. He usually sticks to religious ambivalence or a near atheistic point of view in his films. But this one, Christianity wins (I guess Scott is getting old and is turning back to the Bible), or at least isn't rejected. We're off to meet our maker, who isn't God, but we still believe in God... right? Androids don't worship God, nor do they worship us (they serve us).

If we were created by aliens (because fuck Darwin), then the obvious question is: who created them? More aliens? Who created them? More aliens? It's a vicious cycle that usually terminates with God. God created everything. But when asked who created God, the trump card is pulled, because nothing created God. God always existed. I may believe in God, but the God-trump-all-card is not a worthy argument in scientific debate.

Why is this stupid to ask? Because it has no real answer, and any answer is a cop-out. I call it idle philosophy, a term I get from John Milton. Asking these sorts of questions get us nowhere, at least nowhere satisfying. We either end up with no answer ("I don't know where we came from"), an answer that is a paradox ("We created God who then created us"), or an illogical conclusion, a cop-out ("God did"). This is why Zen Buddhists usually give strange answers to certain questions. If you ask a Zen Master who created us, they would probably respond with "Mu." It's not an answer because there isn't one. If you ask a stupid question you get a stupid answer, so you shouldn't ask them.

Overall the movie was disappointing. It's okay for a movie to ask questions and not answer them, but it is supposed to make us think (something Borges does a lot in his short stories). But to barely give a premise of philosophy, throw around a bunch of vague questions, and NEVER EXPLAIN THE ALIEN! leaves me a bit disgruntled. Are we supposed to be looking at these questions on the origin of life from a religious point of view or a panspermic one? (Because, again, fuck Darwin). Are we supposed to think of ourselves as cattle or a wrongful experiment? Who exactly is the protagonist, so that we can understand which point of view to weigh more heavily? Is it Shaw or David or the Engineers?

Was there even a philosophy? Was there even a plot?

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Forget Thyself

About a week ago I was part of a discussion on authenticity. We were examining the nature of authenticity, and during the discussion we asked the basic question: what is authenticity. It seems rather amazing that a group of educated persons would start a conversion on something as complex and the nature of authenticity and not start with such a basic question. I assume we all assumed we knew what we meant by "authentic."

In the spirit of Rousseau I had assumed that there are degrees of authenticity (such as writing is less authentic than speech, or wife is less authentic than mother, masturbation is less authentic than sex), but only one type authenticity. But through the discussion it was brought up that there are, in fact, different types of authenticity. For instance, there is the classic Platonic idea of the the concept being more authentic than the physically rendered thing; the "thingness" is more important than the "thing" itself. But say it was the other way around, where the concept was less real than the thing itself. For anyone who ascribes to Greek thought, this is rather tough to consider, but it is all a matter a perception of reality.

Take this example from Jorge Luis Borges in his Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, where a fictitious society of people on a planet known as Tlon conceive of no such thing as "thing" or "thingness." Their very language illustrates this, in that in their language there are no nouns. So there is no word for moon, rather it is referred to by a string of adjectives, such as "aerial-bright above dark-round." Imagine a reality in which no thing is real, only by how it is perceived or what is done with it. An American football would simply be called, "long-round leather throw." We have an understanding of a thing because of our understanding of its thingness, where on Tlon their thingness is really a summation of the thingness.

In the case of Tlon thingness is no more less or real than the thing, because in that reality there is no thing, only a consequence of action and description. Thingness and thing are one in the same. So, can we conceive a reality in which a thing is more important, more authentic than its mental conception? Definitely, and it does exist, and we see it everyday; namely, we see it when someone is bullshitting us.

Take for instance the art of post-rationalization. I call it an art because it takes some serious bullshitting to make sense of something completely pointless, arbitrary, and irrational. As a personal example, I decided when I was in high school, senior year, while driving to school, I wanted to be an architect. Why? To be honest, I have no idea. Maybe it was because I had an uncle I never met who was an architect. Maybe it was something about the musical structure of Dream Theater (which I was listening to at the time) that inspired me. Maybe it was because I was good at math and I liked drawing. They are all excuses to a decision that had no rational basis. I decided to be study architecture, and I had no precognitive reasoning why I chose to do so. I make up stories so I actually have an answer to: "Sooooo... why did you want to be an architect?" But really, the excuse is less authentic to the decision. It seems that in anything we do, any choice, any action, the action is more authentic than the explanation.

Why did you forget to set your alarm? [Insert excuse here] is less authentic than the myopic answer of "because I forgot to set it." There isn't a rationale to most decisions, if we make decisions at all. We have come to grasp our lives as a series of choices, when, in fact, most choices are unconsciously already made. We get to the end of a page, we can flip the page or not, but unconsciously the choice is already made to flip the page because we want the story to keep going. When the sun is setting we have the choice to turn on the lights or walk around in the dark. Unconsciously we have already made the choice, because there isn't much of choice there anyway. I would say on a give day the average human probably makes two choices, and those probably largely involve the choice of food.

Or again, these actions and their excuses don't have to be negative, such as in an instance where we take credit for a complete accident. Another personal example would be a building design a friend of mine and I did for a prison in a skyscraper. Our concept was to make a nurturing prison, and, since the primordial concept of nurture is the "womb," we went for the concept of invagination, which would challenge the typical phallic form of a skyscraper. Arbitrarily we took imagines of the uterus and vagina from Grey's Anatomy and cut them up and played with the forms. We picked out which one we liked best, placed two giant spheres on it to represent the ovaries (and to be anti-phallic), and then took a picture and Photoshopped it. Once I was done I showed it to my partner's girlfriend, who said it looked like a giant limp penis, to which my partner said, "Well, then the skyscraper doesn't have any [male] ego!" Then we concocted some bullshit to make the penis-building seem deliberate, when, in fact, it was completely an accident.

All of the above leads me to an article I just read recently, in which the more educated we are the more biased we are. The more educated we are the more shortcuts to thinking we make. We tend to judge others for their biases and their irrationalities, while at the same time forgiving ourselves of similar biases and mistakes; sometimes we don't even know what our biases are. We easily dismiss or excuse a fault of ours, we make excuses for things that need no excuses. We prepare a piece of bullshit to supplant an authentic action.

As it turns out, the more we excuse ourselves, the more we bullshit our way through faulty decisions and actions, the less we understand ourselves. Essentially the study found that the more meditation and self-reflection we do, the more we try to understand ourselves and why we have these faults, the less we understand ourselves. So, not even self-reflection will save us from our shortcomings. More or less, "know thyself" is bullshit. I would say this a direct factor of the type of authenticity in which the thing is more authentic than the thingness. A simple way to put it: the more we bullshit away our actions, the less our actions mean anything, and the more our bullshit explains who we are. And if who you are is primarily understood through bullshit... well, then... I guess that make you a pile of shit.

So from that study, I would say some of the most authentic people are not people who don't bullshit, but rather are stupid people, simply because they are usually too stupid to bullshit (that's a mental shortcut by the way, and completely fallacious of me).

"We spin eloquent stories, but these stories miss the point. The more we attempt to know ourselves, the less we actually understand."

"We spin eloquent stories, but these stories miss the point. The more we attempt to know ourselves, the less we actually understand."

Monday, June 11, 2012

Crazy but not Insane

I was recently taking a gander at the Unabomber Manifesto, a rather extreme, yet fairly spot-on description of societal evolution with technology. While being incredibly psychopathic and disturbing, might I also add that the truth is always disturbing. We all know the old saying, "Sometimes the truth hurts." I feel that that could be shortened to be more accurate: the truth hurts. While reading the introduction to Ted Kaczynski's manifesto I found myself somewhat admiring the man's foresight and forthcoming honesty. He makes no attempt to sugarcoat anything, and though it may be incredibly dark and foreboding, I find that his foresight into how technology will devastate society psychologically is bleakly accurate. When someone makes a statement like the opening paragraph, it's hard to not admire such prophecy, especially since we are seeing his predictions actually occurring. Recently a 22-year old mother murdered her child because he interrupted her playing Farmville. I think it is fair to say Kacynski was right about a number of things.

I felt the same way when I first decided to look up what Hitler's painting looked like. It's a pretty standard fallacy to say, "Well, Hitler was rejected from art school," as if to say he sucked at painting, how could he govern a nation? Two problems arise here, the first being that Hitler's paintings were mostly of buildings. He even says in Mein Kampf that he was told he should be in architecture school, not art school. The second is that when we hear he was a painter, we immediate correlate the person with talent. But when I first saw some of his paintings, I was shocked at how good they were... for a thirteen year old boy. I remember my drawings from the age of thirteen, and I couldn't get linear perspective down while sketching, something Hitler did very well. While his paintings are not spectacular, they demonstrate a great amount of potential for such a young person. Imagine if that potential had been nourished, we might actually be learning about Adolf Hitler in 20th Century Art History class, instead of hearing about him from skinheads.

I discuss these two examples because I have to challenge common thought. Hitler was a bad person, so his paintings must have been awful, when in fact they are quite beautiful. Ted Kaczynski was crazy, so his writings must have been paranoid and demented, when they are actually a fairly accurate prediction of how society's collective psyches will be dramatically changed for the worst.

So I must ask, are these improper assumptions? Is it wrong to say, "Hitler's paintings are quite beautiful," just because he exterminated six million Jews? Is it wrong to say, "The Unabomber's Manifesto is amazingly accurate," just because he was a psychopath and killed a bunch of innocent people? Consider the question a sort of thought exercise in the seven-degrees of separation. Just because Jack knows Kate, and Kate knows John, and John throws his dog in front of a moving train, does that mean Jack is to be judged in the same way John is judged? (I know this is a strawman fallacy, but think of it as a thought exercise). If Hitler made some beautiful paintings as a child, should we judge his paintings in the same way we judge his decision to commit genocide?

I personally think it's unfair. I think we can enjoy Hitler's paintings, or be astonished by Kaczynski's accurate portrayal of technology's effects on the future, and look at those separately from the atrocities these men committed. In no way am I justifying their atrocities, far from it, but I am saying I would like to go to a gallery with Hitler's paintings.

But to make a point, this is not always the case. For instance, I find Charles Manson an incredibly fascinating person, but, to be frank, his music sucks. And to bring Hitler back into the discussion, Mein Kampf was an extraordinarily boring book. It uses almost no metaphor, it's dry, and as a work of literature overall poorly written. Hitler should have stuck with painting or architecture. And even the Unabomber's Manifesto is disagreeable at times. Clearly Kacynski had some animosity toward Harvard professors (can't blame him). His disagreements against political correctness are deserved, but the overall hatred toward liberals, scientists, and activists is quite shocking for someone who went to Harvard.

A painting by Adolf Hitler (yeah, I know... it's really good):

I felt the same way when I first decided to look up what Hitler's painting looked like. It's a pretty standard fallacy to say, "Well, Hitler was rejected from art school," as if to say he sucked at painting, how could he govern a nation? Two problems arise here, the first being that Hitler's paintings were mostly of buildings. He even says in Mein Kampf that he was told he should be in architecture school, not art school. The second is that when we hear he was a painter, we immediate correlate the person with talent. But when I first saw some of his paintings, I was shocked at how good they were... for a thirteen year old boy. I remember my drawings from the age of thirteen, and I couldn't get linear perspective down while sketching, something Hitler did very well. While his paintings are not spectacular, they demonstrate a great amount of potential for such a young person. Imagine if that potential had been nourished, we might actually be learning about Adolf Hitler in 20th Century Art History class, instead of hearing about him from skinheads.

I discuss these two examples because I have to challenge common thought. Hitler was a bad person, so his paintings must have been awful, when in fact they are quite beautiful. Ted Kaczynski was crazy, so his writings must have been paranoid and demented, when they are actually a fairly accurate prediction of how society's collective psyches will be dramatically changed for the worst.

So I must ask, are these improper assumptions? Is it wrong to say, "Hitler's paintings are quite beautiful," just because he exterminated six million Jews? Is it wrong to say, "The Unabomber's Manifesto is amazingly accurate," just because he was a psychopath and killed a bunch of innocent people? Consider the question a sort of thought exercise in the seven-degrees of separation. Just because Jack knows Kate, and Kate knows John, and John throws his dog in front of a moving train, does that mean Jack is to be judged in the same way John is judged? (I know this is a strawman fallacy, but think of it as a thought exercise). If Hitler made some beautiful paintings as a child, should we judge his paintings in the same way we judge his decision to commit genocide?

I personally think it's unfair. I think we can enjoy Hitler's paintings, or be astonished by Kaczynski's accurate portrayal of technology's effects on the future, and look at those separately from the atrocities these men committed. In no way am I justifying their atrocities, far from it, but I am saying I would like to go to a gallery with Hitler's paintings.

But to make a point, this is not always the case. For instance, I find Charles Manson an incredibly fascinating person, but, to be frank, his music sucks. And to bring Hitler back into the discussion, Mein Kampf was an extraordinarily boring book. It uses almost no metaphor, it's dry, and as a work of literature overall poorly written. Hitler should have stuck with painting or architecture. And even the Unabomber's Manifesto is disagreeable at times. Clearly Kacynski had some animosity toward Harvard professors (can't blame him). His disagreements against political correctness are deserved, but the overall hatred toward liberals, scientists, and activists is quite shocking for someone who went to Harvard.

A painting by Adolf Hitler (yeah, I know... it's really good):

Saturday, June 9, 2012

You're Both Wrong

Earlier this evening I was part of a discussion with a group called Putty Club. As the night was drawing to an end we discussed a sort of thought experiment that goes more less like this: if all human knowledge was lost, and the human race had to start over, everything we know in science will eventually be rediscovered (theory of evolution, chemistry, atomic energy, round earth, et cetera), but no religion will be rediscovered. (Who said this, I don't know, nor can I seem to find out).

This is actually a sort of fallacious argument some atheist came up with to say that religion is pointless, and scientific knowledge is eternal fact. But we treated it as a thought experiment and tried to predict the sequence of events that would follow. So the following are our conclusions.

A few things the above statement ignores is things like instinct and the fact that humans are pattern-making beings. We would inevitably create language again, and thus yielding to writing. The human vocal cords can only make a certain number of sounds. Infants can really only make a certain number of vocalizations, most of which are easy to do, such as "da da" and "ta ta." "Ma ma" and "pa pa" are a bit more complex, but nonetheless, these are simple vocalizations, along with clicking and grunting. When writing would develop there would only be three essential and logical ways to visually communicate spoken word: by letter (Phoenician, Greek, Latin), by syllable (Cherokee, Korean), and by word (Mayan, Egyptian).

But humans are pattern makers. We put things together in ways that make sense to us. For instance, once we learn to count and do rudimentary math, we would do what other early literary civilizations did, namely associate written symbols with numbers, like the Babylonians, Egyptians, Hebrews, and Greeks did. We would naturally observe and find patterns that correspond to seasons and the heavens, such as these sets of stars are visible when it's cold, and these sets of stars are visible when everything is in bloom, and the sun is higher when it is hottest, and so forth. We would eventually notice certain stars move around in relation to other stars, which we will notice there are five, and probably call them "wanderers" (planet literally means "wanderer"). Certain observations will be made that children who have seasonal diets between spring and winter during gestation will have different personalities than a child with seasonal diets between autumn and summer. We won't associate these things with food, but will attribute them to the patterns we can actually mark, namely sets of stars (i.e. the constallations). The heavens will initially be perceived to rotate around the earth, though eventually we'll figure out the earth actually spins because of the complexity of how planets move.

We would see everything in our image, as the human body is the easiest way for us to relate to things we don't understand (anthropomorphization). Naturally we would notice that the liver of this man who was mauled by a bear is similar to this flower (i.e. the liverwort), and associate herbal medication between the liverwort and afflictions of the liver (known as sympathetic magic, according to Frazer). We would pull up a mandrake and notice that its roots look like a little human, and associate some sympathetic cure for it, whether correct or not. The same might be done for fertility and orchids (orchid roots look like testicles, as orchid literally means "testicle").

We only need to look at similarities between isolated cultures to see what would almost instantly reemerge. Rites of manhood, the Hunt, alcohol or hallucinogenic plants, astrology, gold as precious, ghosts, constellations (the same constellations), deities, mystery cults, fertility, herb cultures, et cetera; all cultures have some variation of these, and some have striking resemblances to other cultures.

But can mathematics and science be recreated exactly as we have it today? Doubtful. Just like Christianity will never be recreated, there will be a religion similar to it, with a messiah, a dying god, miracles, et cetera. Mathematics will be recreated, but not exactly as it is today. For instance, Base 10 systems might not be used, but instead use Base 8 (instead of counting fingers, we count the spaces between fingers, and there is a culture, whose name escapes me, that does this). Pi might not be based on the radius of a circle, but could be based on creating three tagential circles of the same radius whose centers lie on the circumference of another circle with the same radius (this essentially creates a triangle, in which pi might actually be described as 3, and anything using the radius would be different system that isn't popular to use). Consider it as the difference between using degrees and radians. Degrees are based on the number of days in a year (simplifying it to 360 to simplify a Base 10 system that works with a Base 12 system), in which we can measure the distance a star moves by day. Why use radians then? which are based off of taking the radius of a circle and making that the length of an arc on that circle. Who knows, we might not even use anything remotely similar to Arabic numbers, but use something like Mayan, or worse, Roman. We might not even grow beyond simply using numeric ticks.

The theory of evolution might be discussed quite differently than the way we talk about it. Or even how particle physics work. We attached some abstract and arbitrary ideas to explain certain behaviors of particle, such as "charges." We explain an electron as having a negative charge, a proton with a positive charge, and a neutron with no charge. What is a charge anyway? We have some notion of it, but its an abstract and arbitrary notion attached to certain properties. What if forces were not rediscovered as "charges" or "energy," but as a sort of invisible push. We might explain particle physics as electrons have a backwards push, protons with a forward push, and neutrons with no push. What is that supposed to mean anyway? Tell me charges are not arbitrary and I'll call you a moron. Sure it's the same idea, but our understanding of these things would be quite different, just like the gods would have different names with the same ideas behind them.

Needless to say, atheists are quite naive when they think science and math would be rediscovered as-is, and religion would not be the "eternal truths" (whatever that means) held by today's religious zealots. Math and science would be understand very differently than what we have today, but with similar ideas represented by some very different concepts and metaphors. Likewise, religion would be created with a lot of the same elements, just with different names. It is naive and foolish for anyone to think science and math, which seem so factual and concrete, can be recreated as-is in a vacuum, and myths to suffer a horrible fate of being lost forever.

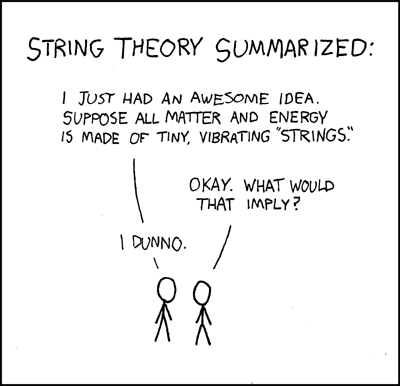

Quite frankly, string theory would probably end up being ridiculously foreign, something like dancing finger theory.

This is actually a sort of fallacious argument some atheist came up with to say that religion is pointless, and scientific knowledge is eternal fact. But we treated it as a thought experiment and tried to predict the sequence of events that would follow. So the following are our conclusions.

A few things the above statement ignores is things like instinct and the fact that humans are pattern-making beings. We would inevitably create language again, and thus yielding to writing. The human vocal cords can only make a certain number of sounds. Infants can really only make a certain number of vocalizations, most of which are easy to do, such as "da da" and "ta ta." "Ma ma" and "pa pa" are a bit more complex, but nonetheless, these are simple vocalizations, along with clicking and grunting. When writing would develop there would only be three essential and logical ways to visually communicate spoken word: by letter (Phoenician, Greek, Latin), by syllable (Cherokee, Korean), and by word (Mayan, Egyptian).

But humans are pattern makers. We put things together in ways that make sense to us. For instance, once we learn to count and do rudimentary math, we would do what other early literary civilizations did, namely associate written symbols with numbers, like the Babylonians, Egyptians, Hebrews, and Greeks did. We would naturally observe and find patterns that correspond to seasons and the heavens, such as these sets of stars are visible when it's cold, and these sets of stars are visible when everything is in bloom, and the sun is higher when it is hottest, and so forth. We would eventually notice certain stars move around in relation to other stars, which we will notice there are five, and probably call them "wanderers" (planet literally means "wanderer"). Certain observations will be made that children who have seasonal diets between spring and winter during gestation will have different personalities than a child with seasonal diets between autumn and summer. We won't associate these things with food, but will attribute them to the patterns we can actually mark, namely sets of stars (i.e. the constallations). The heavens will initially be perceived to rotate around the earth, though eventually we'll figure out the earth actually spins because of the complexity of how planets move.

We would see everything in our image, as the human body is the easiest way for us to relate to things we don't understand (anthropomorphization). Naturally we would notice that the liver of this man who was mauled by a bear is similar to this flower (i.e. the liverwort), and associate herbal medication between the liverwort and afflictions of the liver (known as sympathetic magic, according to Frazer). We would pull up a mandrake and notice that its roots look like a little human, and associate some sympathetic cure for it, whether correct or not. The same might be done for fertility and orchids (orchid roots look like testicles, as orchid literally means "testicle").

We only need to look at similarities between isolated cultures to see what would almost instantly reemerge. Rites of manhood, the Hunt, alcohol or hallucinogenic plants, astrology, gold as precious, ghosts, constellations (the same constellations), deities, mystery cults, fertility, herb cultures, et cetera; all cultures have some variation of these, and some have striking resemblances to other cultures.

But can mathematics and science be recreated exactly as we have it today? Doubtful. Just like Christianity will never be recreated, there will be a religion similar to it, with a messiah, a dying god, miracles, et cetera. Mathematics will be recreated, but not exactly as it is today. For instance, Base 10 systems might not be used, but instead use Base 8 (instead of counting fingers, we count the spaces between fingers, and there is a culture, whose name escapes me, that does this). Pi might not be based on the radius of a circle, but could be based on creating three tagential circles of the same radius whose centers lie on the circumference of another circle with the same radius (this essentially creates a triangle, in which pi might actually be described as 3, and anything using the radius would be different system that isn't popular to use). Consider it as the difference between using degrees and radians. Degrees are based on the number of days in a year (simplifying it to 360 to simplify a Base 10 system that works with a Base 12 system), in which we can measure the distance a star moves by day. Why use radians then? which are based off of taking the radius of a circle and making that the length of an arc on that circle. Who knows, we might not even use anything remotely similar to Arabic numbers, but use something like Mayan, or worse, Roman. We might not even grow beyond simply using numeric ticks.

The theory of evolution might be discussed quite differently than the way we talk about it. Or even how particle physics work. We attached some abstract and arbitrary ideas to explain certain behaviors of particle, such as "charges." We explain an electron as having a negative charge, a proton with a positive charge, and a neutron with no charge. What is a charge anyway? We have some notion of it, but its an abstract and arbitrary notion attached to certain properties. What if forces were not rediscovered as "charges" or "energy," but as a sort of invisible push. We might explain particle physics as electrons have a backwards push, protons with a forward push, and neutrons with no push. What is that supposed to mean anyway? Tell me charges are not arbitrary and I'll call you a moron. Sure it's the same idea, but our understanding of these things would be quite different, just like the gods would have different names with the same ideas behind them.

Needless to say, atheists are quite naive when they think science and math would be rediscovered as-is, and religion would not be the "eternal truths" (whatever that means) held by today's religious zealots. Math and science would be understand very differently than what we have today, but with similar ideas represented by some very different concepts and metaphors. Likewise, religion would be created with a lot of the same elements, just with different names. It is naive and foolish for anyone to think science and math, which seem so factual and concrete, can be recreated as-is in a vacuum, and myths to suffer a horrible fate of being lost forever.

Quite frankly, string theory would probably end up being ridiculously foreign, something like dancing finger theory.

Sunday, June 3, 2012

The Face of All Your Fears

It strikes me recently the level of fear many people have about the supposed on-coming zombie apocalypse. Zombies concern me less than how easily our fears can be manipulated by mass media. In reality, it is little more than cases of cannibalism, which is a frequent occurrence. While it may not be as common as flu outbreaks, there are several reported cases of cannibalism every year. Like shark attacks, it is unlikely to be eaten by a cannibal, but every year a few instances happen. What is different is how mass media has latched onto these recent stories, to play on our fears (and obsession with) of zombies. Like anything else, mass media responds to incentives, and if people want to hear about zombies, they will report on cannibalism.

So what of fear? We believe we should be allowed to live without fear, but like anything else, there is always some appropriate amount that is completely healthy. Is fear healthy? To be frank, yes, it is. How so? Consider this analogy between parents and children with citizens and government.

We all hate those obnoxious children we see in stores or on planes acting up. They are out of control, and the parents have no control over them. Why? Because the parents won't discipline their children. Why? Because the parents are scared of their children. For a child to be raised as a law abiding citizen in society, it is necessary the parents discipline their children. In other words, it is necessary for there to be a healthy amount of fear those children have towards their parents. Do I have a good relationship with my parents? Why yes I do, because I fear my father, as is completely healthy to be.

Likewise, there is a certain amount of fear citizens should have towards their government. It seems that as society evolves from one form of governance to another, our fear towards our rulers changes.

Giambattista Vico in his New Science sets up what is referred to as the "Three Ages of Man," with one extra era that is a result of going through the first three eras. He compares them to the Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages of the Romans (which has a corollary in the Hindu Yugas). The first age is Theocracy, then follows Aristocracy, next Democracy, and finally ending in an intermittent period of individualism or Anarchy, and then we cycle back to Theocracy. When each era is analyzed based on where fear is directed, we can see how fear and governance evolve together.

First, in a theocracy our fears are not directed towards any human, at least not directly. We may fear the Inquisition or the Pope, but only indirectly through our fear of God. When society evolves into an aristocracy our fears move from God toward the people who we work for, and therefore those who provide for us. Since the aristocracy is usually under the rule of a monarch, the aristocracy usually fear the czar, emperor, or king; all the while the people love the monarch. When the people fear the monarch, usually this indicative of a tyranny.

Finally, when fear of those we work for, as in the proletariat's fear of their employers, moves from the aristocracy towards the heads of state, we hit a democracy. In this case there is an equal fear among the wealthy and the working classes toward their government. Of course, when no one fears their government, but the other way around, we have a society full of obnoxious brats like those children on planes. This is anarchy.

It not only lies in governance and parenting, fear lies in law enforcement, the work place, school, on the internet, et cetera. Charles Mason was right in a way, when he believed fear was the most useful tool humans have. Otherwise, we would end up a society of ingrates, though the sad thing is that we are practically already there.

In a very roundabout way, there is certain degree of Stockholm Syndrome that is necessary among everyone for society not to have a complete and total collapse. At what point does healthy fear cross into tyranny, or healthy fear cross into anarchy is subjective to culture and history. Needless to say, fear is not a bad thing. I suppose that's why fear exists.

"The face of all your fears... all your fears unleashed."

~At the Gates

So what of fear? We believe we should be allowed to live without fear, but like anything else, there is always some appropriate amount that is completely healthy. Is fear healthy? To be frank, yes, it is. How so? Consider this analogy between parents and children with citizens and government.

We all hate those obnoxious children we see in stores or on planes acting up. They are out of control, and the parents have no control over them. Why? Because the parents won't discipline their children. Why? Because the parents are scared of their children. For a child to be raised as a law abiding citizen in society, it is necessary the parents discipline their children. In other words, it is necessary for there to be a healthy amount of fear those children have towards their parents. Do I have a good relationship with my parents? Why yes I do, because I fear my father, as is completely healthy to be.

Likewise, there is a certain amount of fear citizens should have towards their government. It seems that as society evolves from one form of governance to another, our fear towards our rulers changes.

Giambattista Vico in his New Science sets up what is referred to as the "Three Ages of Man," with one extra era that is a result of going through the first three eras. He compares them to the Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages of the Romans (which has a corollary in the Hindu Yugas). The first age is Theocracy, then follows Aristocracy, next Democracy, and finally ending in an intermittent period of individualism or Anarchy, and then we cycle back to Theocracy. When each era is analyzed based on where fear is directed, we can see how fear and governance evolve together.

First, in a theocracy our fears are not directed towards any human, at least not directly. We may fear the Inquisition or the Pope, but only indirectly through our fear of God. When society evolves into an aristocracy our fears move from God toward the people who we work for, and therefore those who provide for us. Since the aristocracy is usually under the rule of a monarch, the aristocracy usually fear the czar, emperor, or king; all the while the people love the monarch. When the people fear the monarch, usually this indicative of a tyranny.

Finally, when fear of those we work for, as in the proletariat's fear of their employers, moves from the aristocracy towards the heads of state, we hit a democracy. In this case there is an equal fear among the wealthy and the working classes toward their government. Of course, when no one fears their government, but the other way around, we have a society full of obnoxious brats like those children on planes. This is anarchy.

It not only lies in governance and parenting, fear lies in law enforcement, the work place, school, on the internet, et cetera. Charles Mason was right in a way, when he believed fear was the most useful tool humans have. Otherwise, we would end up a society of ingrates, though the sad thing is that we are practically already there.

In a very roundabout way, there is certain degree of Stockholm Syndrome that is necessary among everyone for society not to have a complete and total collapse. At what point does healthy fear cross into tyranny, or healthy fear cross into anarchy is subjective to culture and history. Needless to say, fear is not a bad thing. I suppose that's why fear exists.

"The face of all your fears... all your fears unleashed."

~At the Gates

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)