Recently I was reading a few books on the Kabbalah tradition known as Gematria. This practice involves taking Hebrew letters and deriving their numeric values (since every Hebrew letter is associated with a number, like Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek letters), and with those values comparing them to other words or phrases with the same numeric value. For instance, the following words or phrases all have the same numeric value of 666:

"Let there be light"Since 6 x 6 x 6 equals 216, the following have a numeric value of 216 (or 216 x 10^x):

"Transmission"

"The heart, the soul, the mind"

"Jehova God that created the heavens"

"The head of the corner" (as in "cornerstone")

"Sarapis"

"I am God on Earth"

"From God"

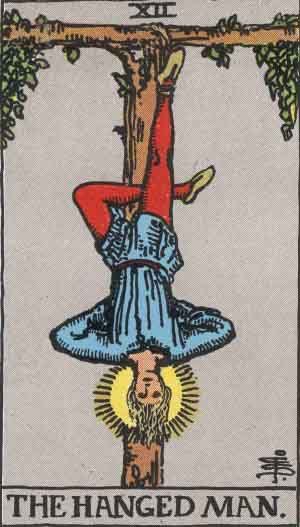

"The stone which the builders rejected" (a common term for the "philosopher's stone")Then, of course, we could rearrange the numbers and look for words or phrases with those numeric values, or rearrange the letters in the words or phrases and come up with new connections, which is a tradition called Temurah. We could double numeric values or half them, and derive new meanings. Thus 432 (216 x 2) would have a certain connection to words or phrases with 216 or 108 values. These studies are suppose to bring its adepts closer to God, understanding God's creation, and find the name of God. Some Kabbalah studies actually assert that rearranging the Torah will give the name of God and the key to the cosmos... something like that.

"Strong"

"Lion" (as in the Lion of the Tribe of Judah)

Is there any actual significance here? Is there any actual meaning behind these traditions? Of course, numbers and letters have no natural meaning, but only the power we give them from our own minds. But let's look at these in connection with practices used today in science: biology.

DNA, the genetic constitution and blueprint of every feature of an organism's physiology, is quite similar to Temurah. DNA is essentially strands of proteins, amino acids, and nucleotides arranged in certain combinations. What makes DNA unique as compared to other protein strands is that when an enzyme translates a DNA strand, the translation is identical to the original. There are four nucleotides: A, T, G, and C. A's translate into T's, and G's into C's, and vice versa. Geneticists play with these four nucleotides, their combinations and translations to manipulate physio-biological traits in, say, a grape plant so that it will be seedless. They compare and relate these manipulated mutations and stands in a number of ways. But is there a difference between reordering 22 Hebrew letters and their numeric values with rearranging ATCG? Not really. The only difference is ATCG will give us results we can observe, while rearranging the Torah is little more than rearranging the Torah.

Is another example in order? I believe so. What about M-Theory? M-Theory is rather complex, but the gist of it is: everything (matter, energy, and empty space) is made up of vibrating strands of energy (string theory), which all act in a certain harmony to yield a potato, or mitosis of cells, or dark matter, et cetera. M-Theory is an attempt to produce a Unified Field Theory, which is essentially a way to link the very large (galactic movement) with the very small (particle physics), as well as link the four forces of weak and strong nuclear, electromagnetism, and gravity. The first three have already been been proven to be linked, but gravity still proves to be problematic. More or less, the whole thing is a search to link all things together.

The Unified Field Theory isn't a new idea, not really, as the Philosopher's Stone is more or less the same thing. Hermeticists believe all things are linked through a number of levels of states, which all are based upon the proceeding level. So, the world of Plants rests below Animals, Animals below Humans, Humans below Gods. Their links are rather enigmatic and paradoxical, so I will avoid not doing the whole study justice by trying to explain something I don't entirely understand.

So what about the Philosopher's Stone? Consider it a sort of Higgs Bosom in alchemical traditions. The Higgs Boson is a theoretical particle that is thought to give matter mass (as opposed to remaining a state of energy, as in E=MC^2). The Philosopher's Stone is believed to be the most basic piece of matter, while also being the highest and most perfect. It has the ability to perfect other substances, such as perfecting a base metal, such as lead, into a perfect metal, such as silver or gold. It is produced by killing and reviving a substance, such a sprig of pine, absorbing its oils and producing a salt, then burning it to a white ash, mixing it with its own oil, and some other secret operations to produce the "stone which the builders rejected." It's a lot of mystic allegory with some actual science, but we can begin to see how science is really an extension of ancient traditions.

Hermeticists have had the idea of Relativity long before Einstein, and the Egyptians had psychology and psychoanalytics long before Freud or Jung. Kabbalah has been playing number theory games for centuries, such as root numbers or perfect numbers. Could we not consider science and mathematics as a continuation and extension of some old traditions?

The funny thing is that most alchemists and Hermeticists feel that science is doing their jobs for them, leaving the meaning to be understood to be done by alchemists. Strange how that works.